(New York University, USA)

From Creative Commons to Local Contexts: The Passamaquoddy Connection

In March 1890 Jesse Walter Fewkes made 31 wax cylinder ethnographic recordings with members of the Passamaquoddy community in Calais Maine. These were the first recordings of Native America ever made in the United States. In 1890, the legal protections that were in place for sound recordings were minimal; sound recordings were treated as property proper, which gave Jesse Fewkes exclusive property over these, in perpetuity. When sound recordings came under federal US copyright protection in a special amendment in 1971, these first recordings were also brought into federal jurisdiction and are now protected by copyright until 2067, when they will enter the public domain. Because they are not the ones who physically made the recordings, the Passamaquoddy community has no legal rights to any of these materials, even though they contain Passamaquoddy songs and stories sung by Passamaquoddy people, that only the Passamaquoddy can understand and interpret in culturally and linguistically significant ways.

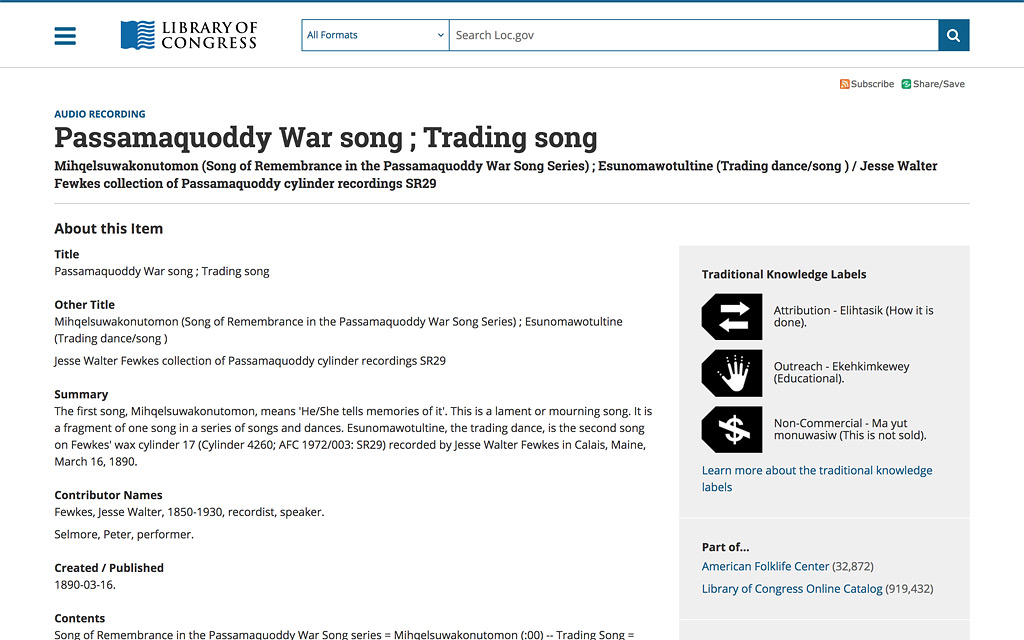

In 1970 these cylinders were transferred from Peabody Museum of Ethnology and Archaeology at Harvard University to the American Folklife Center (AFC) at the Library of Congress through the Federal Cylinder Project.[ 1 ] In 1980 these recordings were returned for the first time to the Passamaquoddy community on reel-to-reel tapes. Because of the poor quality of the sound, only 4 cylinders could be identified and translated. In 2015, the Library’s National Audiovisual Conservation Center (NAVCC) included these cylinders in their digital preservation program for American and Native American heritage. Using up-to-date technology, notably the Archéophone cylinder playback machine (invented in 1998 in France by Henri Chamoux), sound engineers were able to extract the content directly from audio cylinders to digital preservation master files. The digital files were then restored and enhanced, using the Computer Enhanced Digital Audio Restoration System - CEDAR. At the same time as this preservation work was initiated, the AFC, Local Contexts project (www.localcontexts.org) and the Passamaquoddy Tribe joined together for the Ancestral Voices Project funded by the Arcadia Foundation. This project involved working with Passamaquoddy Elders and language speakers to listen, translate and retitle the recordings; explaining and updating institutional knowledge about the legal and cultural rights in these recordings; adding missing and incomplete information and metadata; fixing mistakes in the Federal Cylinder Project record and implementing three Passamaquoddy Traditional Knowledge (TK) Labels (see below). These add additional cultural information to the rights field of the digital record and provide ongoing support for how these recordings will circulate into the future. (See: loc.gov/item/2015655578)

In April 2018, the first Library of Congress online record with this updated and new metadata for one of the cylinders was publicly released. This new record includes the Passamaquoddy TK Labels, the Passamaquoddy names of the songs included in the catalogue record, enhanced traditional knowledge about the songs and a direct pointing of the authority over these songs back to the Passamaquoddy community who have developed their own Mukurtu Collection Management System (see mukurtu.org) instance to share these recordings as well as a range of other cultural heritage (passamaquoddypeople.com/).

This preservation and access project is one example of a new movement where institutional knowledge about the legal and cultural issues affecting Indigenous collections directly impacts decisions made around digitization and access wherein a descendent community is directly engaged. Education and training that the Local Contexts team delivered to the American Folklore Center led to the development of this new preservation and digitization process which importantly, allowed for a radical update of the historical record for these recordings.

Native American cultural heritage collections are unique in composition, content, in their social and cultural value to the communities from where they derive and to non-Native publics seeking to better understand the complexity of Native cultures and cultural practices. In a post-NAGPRA[ 2 ] institutional landscape, the lack of legal rights for Indigenous communities over cultural heritage that was documented by non-Indigenous others, and that is now located within cultural institutions nationally, has produced significant challenges for institutions. This is in regard to ethical decision-making around preservation and digitization; for providing culturally appropriate access; and for respectful engagement and trust building between communities and institutions.

One of the most consistently problematic areas for collecting institutions is in the negotiation with communities over the legal, ethical, and cultural rights to these collections as this affects preservation and access decisions: who owns them, who controls them and who should access them now and in the future? Unlike other collections, Indigenous cultural heritage is caught-up in various legal regimes of protection that are difficult to understand and untangle, even for the most seasoned legal counsel. But this is no longer just a registrar problem. In their increasing movement into digital formats, the new rights that are generated only compound the problems for collection managers, for curators and for other staff with responsibilities to respond to Native concerns about ownership and circulation of materials. These legal entanglements can impede access and use and make already difficult negotiations with communities and other rights holders even harder.

Local Contexts:

Local Contexts is a digital initiative and movement that is responding to certain failures within copyright law specifically and intellectual property law generally. The problem of copyright that we encounter and informs the Local Contexts project is that copyright has functioned as key tool for dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their rights as holders, custodians, authorities and owners of their knowledge and culture. Copyright, as a tool of colonial dispossession facilitated the taking of Indigenous knowledge and culture, which in recorded form (photographs, sound-recordings, dictionaries, field notes) became owned and controlled by others including researchers, scholars, government officials. This has meant that Indigenous peoples have not had any control over their culture and its representation in a diverse range of contexts. Stephen Kinnane (Miriwoong Gadjerong) has eloquently explained the problem of documentation and ownership resting with researchers and colonial authorities:

Until the early 1990s when Aboriginal people such as myself started documenting our communities in film, there was an estimated six thousand hours of material created about our communities [in Australia], of which perhaps ten hours actually involved some Aboriginal input. It is the same with the images that were taken to document our communities in missions, in Settlements and in camps – they are not the images that we would have chosen to represent ourselves. Shadow Lines 2004, 257.

The Local Contexts initiative began in 2010 when Kim Christen and I started to think more carefully about how to support Indigenous communities to address the immense and growing problems being experienced with copyright around Indigenous or traditional knowledge. We had both been working with Indigenous peoples, communities and organizations over a long period of time and had increasingly been engaged in a very specific way with the dilemmas of copyright that existed at the intersection of Indigenous collections in archives, libraries and museums. Combining both legal and educational components, Local Contexts has two objectives. Firstly, to support Indigenous decision-making and governance frameworks for determining ownership, access to and culturally appropriate conditions for sharing historical and contemporary collections of Indigenous material and digital culture. Secondly, to trouble existing classificatory, curatorial and display paradigms for museums, libraries and archives that hold extensive Indigenous collections by finding new pathways for Indigenous names, perspectives, rules of circulation and sharing culture to be included and expressed within public records.

Inspired by Creative Commons (CC) we began trying to address the gap for Indigenous communities and copyright law by thinking about licenses as an option to support Indigenous communities. Our initial impetus was to craft several new licenses in ways that incorporated local community protocols around the sharing of knowledge. Pretty quickly however we ran into a significant problem: with the majority of photographs, sound recordings, films, manuscripts, language materials that had been amassed and collected about Indigenous peoples, and that were now being digitized, Indigenous peoples were not the copyright holders. Instead copyright was held by the researchers, missionaries or government officials who had done the documenting or by the institutions where these materials were now held. Or – at the other end of the spectrum, these materials were in the unique space that copyright makes – the public domain. This meant that not only did Indigenous peoples have no control over these materials and their circulatory futures, they could not apply any licenses – either CC ones or ones that we were developing. This was a problem that we responded to by developing the TK Labels.

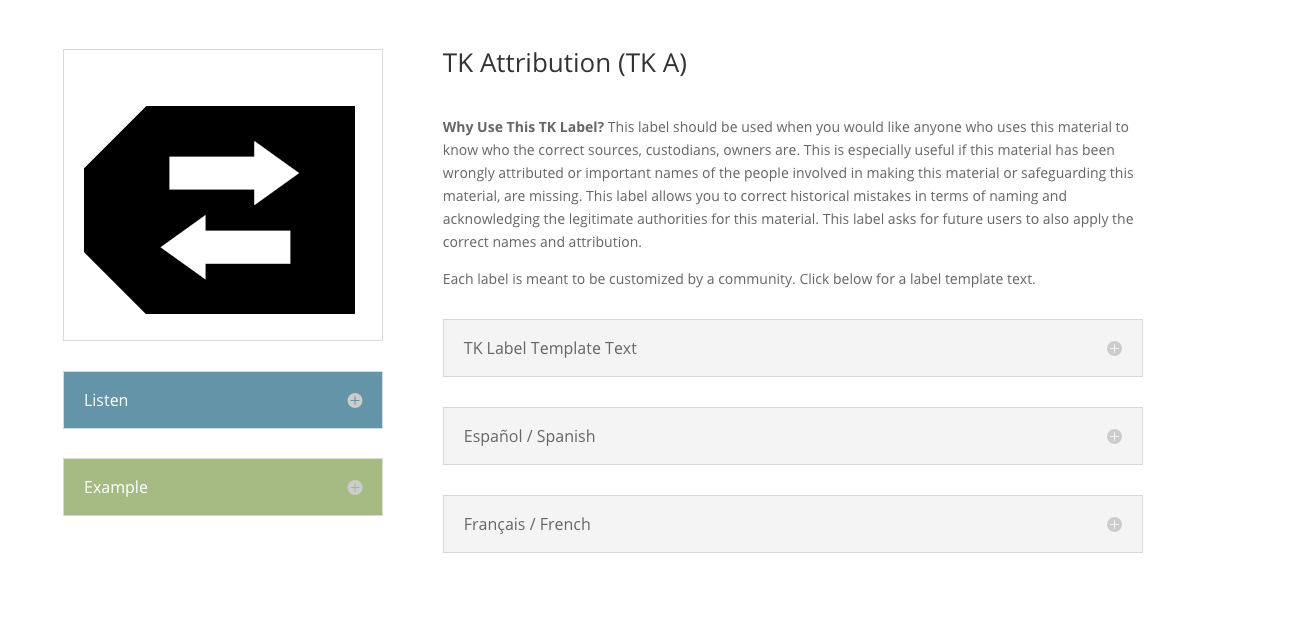

The TK Labels are educative digital tags that are able to reflect cultural protocols around the circulation of knowledge.

TK Labels function as social and educational guides for action and the proper use of Indigenous materials established by Indigenous communities themselves. TK Labels signal a set of cultural parameters for access and circulation. They ask people to think about how these collections came to be created as well as their actions of using these materials, carefully and thoroughly. As an educative intervention rather than a legal one, the TK Labels cannot restrict material, but they can point to instances where there was no or limited consent for the recording or collection of material, and that should affect and change how it gets used in the future. The TK Labels allow for the inclusion of historically missing information about source communities, for instance the name of the community from where it derives, what conditions of use are deemed appropriate, how to contact the relevant family, clan or community to engage with discussions about collaborative future use. The TK Labels and TK Licenses are resources that foster more appropriate understandings about the use and circulation of Indigenous knowledge and culture. They also work to rearrange relationships of power and inequality that Indigenous peoples experience in their relationships with the institutions that hold and control Indigenous heritage. They also encourage different possibilities of engagement with Indigenous communities by non-Indigenous users of this kind of material into the future.

Our point of departure from Creative Commons, and probably why CC has not been able to address the unique problems that Indigenous peoples experience in relation to copyright – is that copyright excluded Indigenous peoples and classified Indigenous peoples and cultures as open to taking and using without any regard for cultural differences in access, use and circulation. For Indigenous peoples, research and access are not experienced as a universal good – especially for communities who have been subjected to extreme conditions of study, collection and analysis as part of colonial research agendas. As the Maori scholar Linda Tuiwai Smith explains in her book Decolonizing Methodologies, for Indigenous communities research is experienced as a dirty word, as it has been a vehicle for extreme loss as well as harmful representations that informed policy and continues to affect Indigenous peoples lives. Research has been a tool of colonialism, a form of taking predicated on access that precludes Indigenous circulation routes or proper consents. So, ongoing universal access to that research prompts a question about equity in the initial collection and also inevitably in its futures of digital circulation.

Copyright law is a culturally specific law that erases difference. Responses to the limits of copyright law – access, openness and commons – repeat the foundational exclusion upon which copyright law is built. Neither asks about, or is cognizant of, the multiple pathways for and contexts under which the production of knowledge take place. As a fundamentally colonial instrument, copyright law reproduces a romantic and totalizing idea that knowledge is produced outside of local contexts and the relationships that give it meaning. Local Contexts takes the universal as one starting point for thinking more critically about concepts of the commons and promotion of undifferentiated access. Local Contexts asks for histories of colonialism in research and study, where Indigenous peoples became ‘subjects’ for white projects of knowledge accumulation to be addressed in a substantive way. Universal access is not necessarily equitable access. A key question for us in this access conversation remains “access to what?”

- [ 1 ]

- www.loc.gov/collections/ancestral-voices/about-this-collection

- [ 2 ]

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act