(Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Germany)

Postcolonial digital collections: Indian examples

Digital archives and online collections have the potential to reach large audiences and to grant access to heritage material formerly stored and locked away in depots and storage rooms. Museum and archival content is for various stakeholders often physically distant, and it requires resources to get close to and consult it. Furthermore, they are subject to more or less comprehensible gate-keeping policies. Online representation can be a way to overcome these established visual economies. When digitization and online dissemination is considered in ethnographic collections, digital archives in addition to this come with a strong notion of postcolonial practice. As a number of digitization projects have stated, to make content accessible online is also understood as a form of sharing content potentially with so called ‘source communities’. It is a way to foster encounters, to vividly evocate the common cultural heritage, and to research in partnership. As Clementine Deliss, the former head of the Frankfurt ethnographic museum put it, museums need a form of remediation: a correction or healing of the colonial past’s resonation. This requires exhibiting against the grain of ethnicity or tribe, the acknowledgment of earlier exhibition and collection narratives, a critical integration of the same into contemporary work, and a change in methods of communication (Deliss 2014). Opening the drawers and shelfs and communicating to the potentially largest audiences what is in store, is one step in this direction.

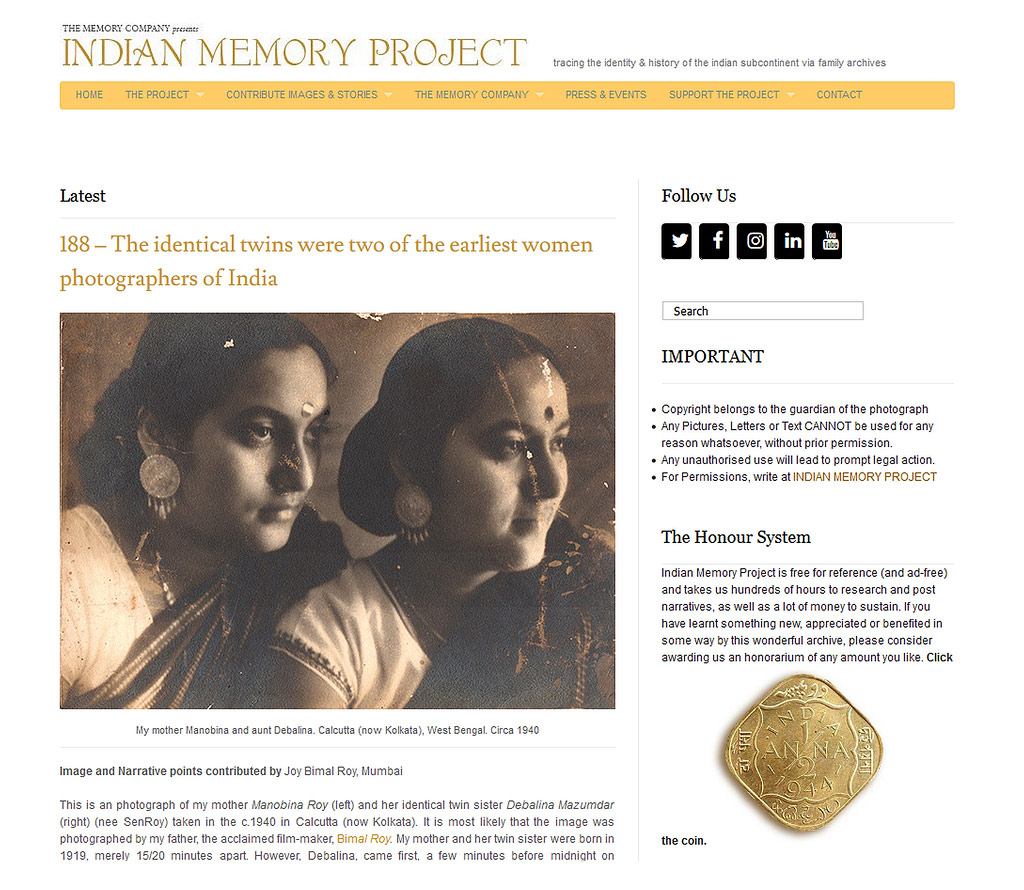

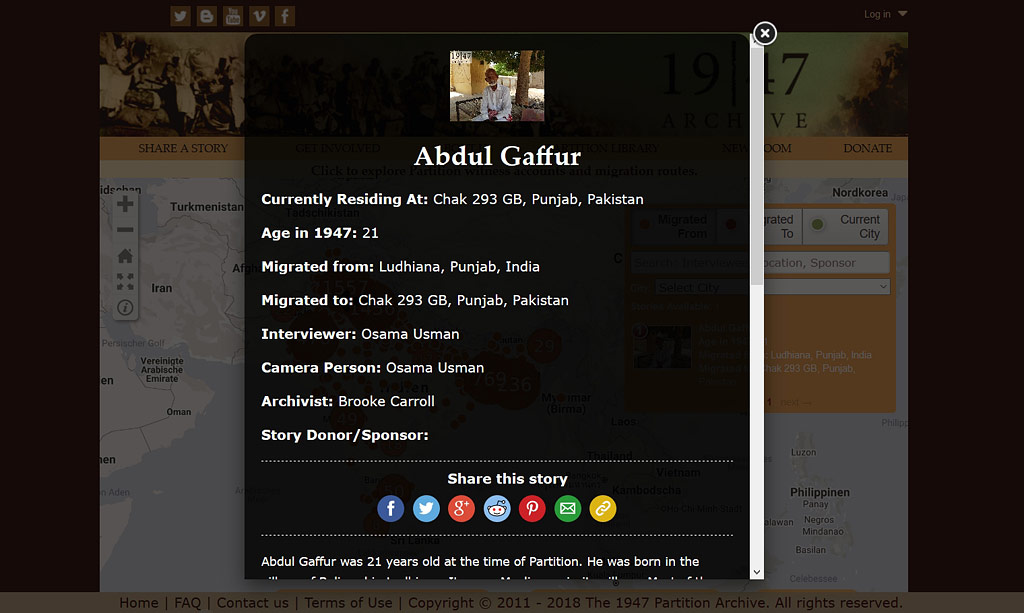

However, my research on digital archives with content originating in India shows that this postcolonial agenda does not necessarily result in the envisioned outcomes. Actual online encounters on heritage material seem to follow different logics, and to not adhere to postcolonial agendas of Euro-American institutions (as necessary and important as these are). I worked very closely with the 1947 Partition Archive and Indian Memory Project, two digital-born archives. While the 1947 Partition Archive records and preserves video interviews of people who lived through the partition of India and Pakistan, Indian Memory Project assembles historic photographs and disseminates them along with a narrative that the contributor tells about the photo.

Noticeably, it is for both archives highly educated Indian (stemming) women that initiated the projects and lead them until today. Forms of dissemination differ slightly between the two digital archives: Indian Memory Project sees most traffic and communication in the comment section of its own website, while the 1947 Partition Archive has a large and active crowd of followers on Facebook. But both are able to generate encounters and to foster a vivid exchange on the past. That the basis for this are newly recorded accounts (in the case of the 1947 Partition Archive) or documents gathered for in a crowd-sourced way (as for Indian Memory Project), rather than long-term centrally preserved collections, seems to be of little concern for the online crowd. What matters instead is the evocation of memories and the emotional involvement that these two online archives allow, creating empathy at a distance on the ground of personally meaningful stories.

What is more, the two archives compel us to rethink the understanding and usefulness of intercontinental digital returns as a postcolonial agenda. Both the 1947 Partition Archive and Indian Memory Project formed out of a felt need of access to the subcontinent’s past. It was the perceived neglect of a national public discourse on the topic, and the notion that resources and documents are kept under lock and key in national archives. Both Indian Memory Project and the 1947 PartitionArchive do not so much target international archives and collections with their critique, but national Indian (and to some extent Pakistani) institutions. Claims about an unjust treatment in international access policies are rare. There is either no knowledge about large collections laying oversees or access is at least provided for non-commercial use, increasingly also in online forms. Indian institutions like the National Archives, on the contrary, often conceal their content and disallow access or even information about what is in store. Hence, when Anusha Yadav, the founder of Indian Memory Project, states that her project is about sharing and openness, she also formulates a critique deprecates visual economies that have their origin in colonial times. The Indian national and state archives were founded during the British Raj, and the formerly applicable storing and history making conventions endured also after independence. Overcoming these is the talk of the day, through novel archival forms and through active involvement of larger online crowds. Newly created digital archives are not least projects of undermining conventions determined by colonialism. The ‘post’ in postcolonialism refers not to scrutinizing the past, but the conventions that enabled it and the continuities of it. This postcolonial agenda partially ignores European efforts of digitizing Indian cultural heritage, and instead focuses on current problems within the subcontinent, its national governments and the voices from within.

Reference:

Deliss, Clementine (2014): Entre-Pologiste. Das ethnografische Museum als Experimentierfeld, pp. 435-450. In: Parzinger, Hermann, Stefan Aue and Günter Stock (eds.): ArteFakte: Wissen ist Kunst – Kunst ist Wissen, Bielefeld: transcript.