(Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany)

Living things in Amazonia and in the museum – Sharing knowledge in the Humboldt-Forum

The foundations of this work were laid in 2014 at the Humboldt Lab Dahlem. The Humboldt Lab was a space to experiment, and to discuss the future of ethnographic museums in Germany. It was intended as support for the Humboldt Forum, the highly politicized, large-scale new exhibition space for the Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Asian Art in the center of Berlin.

Everybody at the Humboldt Lab seemed to be talking about multiperspectivity. It was deemed an important, if not essential aspect of postcolonial curating. Yet, I could not see many people actually practicing multiperspectivity. So I proposed this project to the Humboldt Lab: a collaboration with an indigenous university in Venezuela, albeit in a digital format. The idea was to share parts of the collection from the Amazon with indigenous students from different ethnic groups via an online platform, which we would jointly develop during the project. This collaboration could later be displayed at the museum, to transport other perspectives on the collections into the exhibition space, too.

The basis of such a project is my conviction that opening ethnographic museum collections to members of so called “source communities” is a necessity and central to museum work, and that well-made digital tools can be very useful in this respect. It should go without saying that there is no legitimacy to preserve historical ethnographic collections without sharing this heritage.

My personal goal with the project was to build long-term collaborative and mutually fruitful relationships between museums and indigenous stakeholders in the Amazon region. This would help me not least to learn more about the collection, especially about the meaning of the objects for today's communities. And a digital database would allow a shift away from the past and ancestral knowledge to actively work with digitally affine young people "between the worlds", who could take on the role of mediators to communicate knowledge of their communities and elders in novel formats.

After a pilot at the Humboldt Lab (2014-15), the project started with funding from the Volkswagen Foundation in May 2016. My project partners are people working at initiatives of (higher) indigenous education or for indigenous organisations in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela. When we started the project, our focus was on collections of the Pemón and Ye'kwana, who are represented at the Indigenous University of Venezuela. Over time, we also included collections from the upper Rio Negro region (Brazil/Colombia).

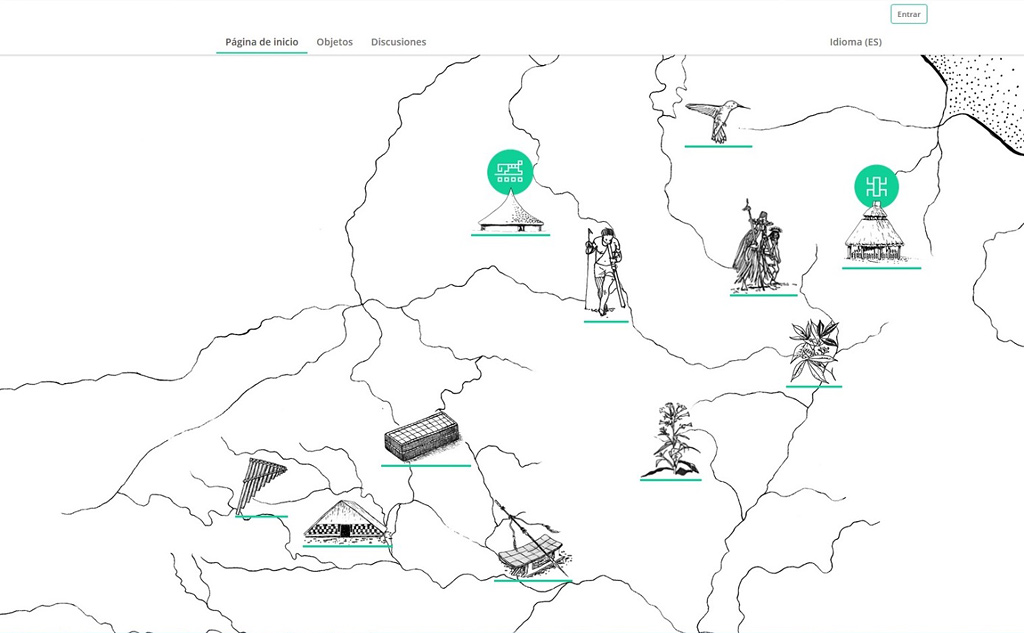

We developed the concept for the online platform during the visit of the first indigenous delegation to the Berlin museum in September 2014. The platform now looks as follows:

The starting page shows a sketched map of the region where the collections stem from, enhanced with symbols. The symbols are ethnic ones – mainly depicting traditional houses but also important rituals – because the students classified the objects according to ethnic group and according to context of use. The object pages feature further symbols. We chose to work a lot with symbols rather than written text to make the Spanish language – our medium of common communication – not too dominant. The platform in general is multilingual: editing is possible in German, English, Spanish, Portuguese, and in eight indigenous languages. The content and the user interface, however, is still far from being completely translated into all languages.

Clicking on one of the symbols on the start page takes you to thematically filtered object lists, which in turn refer to individual object pages.

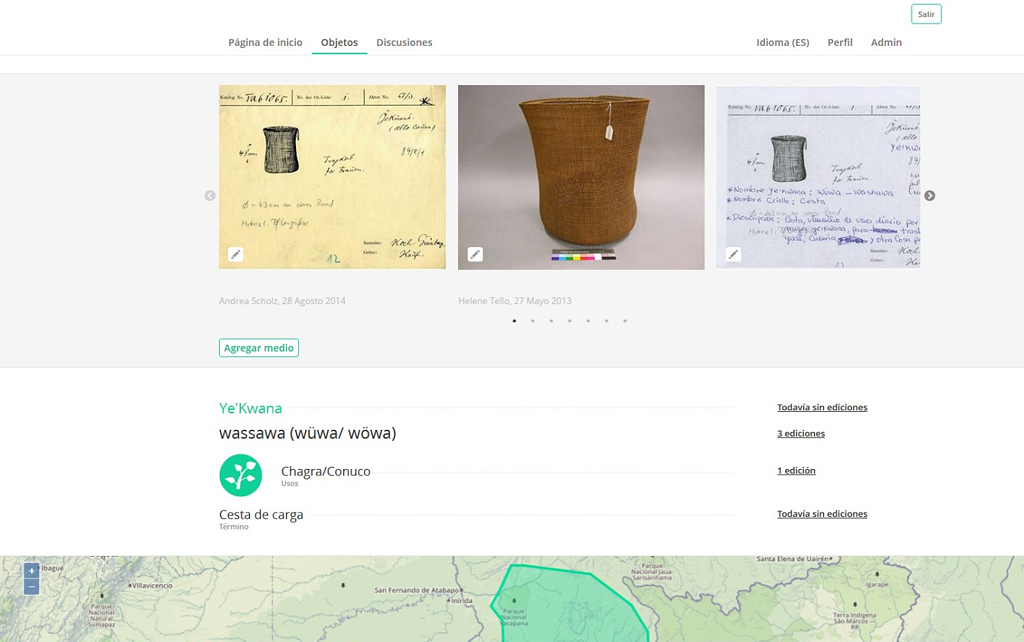

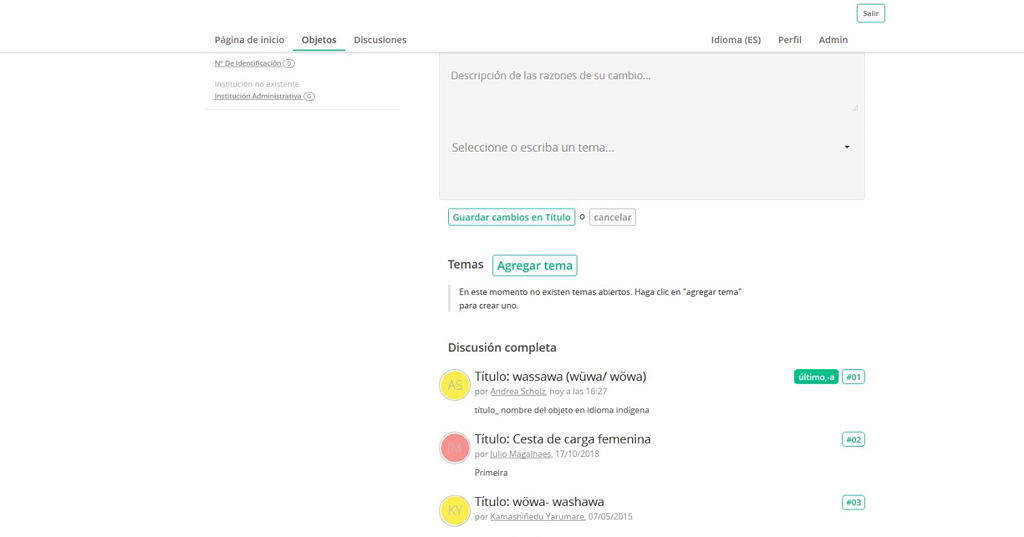

This object, for example, is a carrying basket of the Ye'kwana. The upper part of the page is intended for media files. Beside the object photo and the original index card registered users can upload as many photos, audio and video files as they like. This is a very important aspect, as the indigenous partners have pointed out from the beginning that it is important to show the "practice" around the objects, i.e. from the procurement of materials to the production and use. This media collection is followed by the ethnic classification, the name of the object in the respective indigenous language, the context of use, and the general object term (according to the priorities set by the indigenous partners).

Initially, the platform was open to registered users only. Now there is a public version online that everybody can consult. Editing an object or typing in information is only allowed to registered users. All editions and changes are stored and visible; knowledge is therefore never concluded, but always understood to be negotiable.

Taken together, the platform meets the needs formulated at the beginning of the project. In contrast to the Berlin museum's internal database or the online collection database ‘SMB digital’, it allows collaborative research on the objects and acknowledges indigenous knowledge systems.

However, some problems remain unresolved: Since the museum’s main internal database lacks an interface we can currently export data to the “Sharing Knowledge” platform only via excel files. Furthermore, the platform is missing an offline version that can be easily synchronized. Quite a few of the partner institutions have problems with internet access; hence we created an offline copy of the platform for consultation. It is supplemented by paper forms, which people fill and sent as scans to me via WhatsApp. This somewhat obscured mode of working on the database proofed to be working best for us.

In future, the “Sharing Knowledge” platform and similar projects would benefit from a digital architecture that is even better adapted to the user community needs. As I understand it, this would include abandoning the museum logics of arranging objects, that is still reflected in the "Sharing Knowledge" platform and database. "Sharing knowledge" currently functions as a document management system, and information within the object pages (e.g. on materials or geographical-historical references) cannot be linked to each other, but rather must be re-entered each time an edit is done. Through many years of cooperation with indigenous partners, I have understood that the objects cannot be separated from the wide range of practices associated with them. These practices, in turn, are directly linked to the territories where the primary materials are collected and traded, and where the objects are produced and used. Provenance in an indigenous sense thus refers to "source communities", but also to myths around materials and objects.

All these themes find no place in the Western logic of object classification. An ideal collaborative digital platform would allow such multiple connections of territories, people, and stories. In this way it would be possible to more adequately represent the universe in which objects and the associated knowledge circulate, both in the museum and in the indigenous communities. Technically, this is possible with graph-based databases. Ontologies for these databases have to be written on the basis of intense collaboration. Such postcolonial digital connections are a basic requirement for the decolonization of museums and knowledge systems.